In short: you don’t have to.

But…

Let’s first understand the difference between sound and music.

The sound we call ”La” is produced when a string vibrates 440 times per second. The note La exists naturally, but in this raw form, it doesn’t carry meaning for us. Sounds become music only when they are organized into a rational structure that gives them purpose.

When rivers flow or birds sing, they produce sound—not music. When sounds are arranged according to melodic, rhythmic, and harmonic structures, they take shape as music. Music theory is the study of these structures.

The primary aim of learning music theory isn’t to memorize notes or abstract concepts, but to understand the network of relationships underlying the music. Every note, every chord, and every rhythmic pattern gains meaning only in context. A single note, on its own, is only a vibration, but its relationship with others transforms it into an emotion, an expression, and ultimately, a form of storytelling.

This brings us to one of the core principles of neuroscience:

Our mind does not map isolated parts, it maps the relationships between them.

From a neuroscience perspective, brain doesn’t store information as isolated parts, but encodes the position, sequence, relationships, and context between them:

- The visual system doesn’t represent objects as individual pixels, but through edges, shapes, color relationships, and movement directions.

- Memory systems don’t store isolated events, they store the causal and temporal links between those events.

- The hippocampus and associated structures don’t organize things, they organize the connections between things.

From music theory perspective, music is not the art of individual notes, but of intervals between notes, functional relationships between chords, and rhythmic patterns:

- A single note holds no natural meaning; it gains meaning through its placement among others, via sequences, tension and resolution, expectation and surprise.

- Music theory maps out these relationships, just like the brain represents sensory data as a network of connections rather than isolated facts.

A whole is not merely the sum of its parts; it is the knowledge of the patterns that connect them. That’s what we call information.

Learning music theory allows us to recognize those very patterns. Just like the mental representations our brain uses to interpret the world around us, everything we hear in music finds its place on the mental map we’ve developed over time.

If you have never studied music theory before or had basic training at school, learning theory and becoming familiar with the terminology may feel difficult at first. To make sense of the information, you need to be able to see the bigger picture. This is why trying to explain or understand a closed and interconnected system like music theory can be challenging. But if you can get through what is often called the “beginner’s hell,” you may experience an awakening similar to Neo’s. : )

I often compare this process to dropping someone blindfolded into the middle of a rainforest with a parachute. A system exists all around you, and at the micro level everything is interconnected. Yet in the beginning, you may perceive it as chaos and simply ask, “Where have I ended up?” because your mind is encountering this environment for the first time and has no existing mental framework to understand it. This is where the importance of mental representations comes into play:

——————————————–

Mental Representations and Musical Meaning

We all rely on mental representations. Mental representations are patterns of information—such as images, rules, relationships, collection of information or something more abstract—stored in procedural memory and used to generate quick and effective responses when needed.

Let’s say you’re thinking of a beach. This image in your mind is a mental representation. Most people can see the beach in their minds. But there’s a big difference between someone who has spent a day at the beach—swimming, reading, feeling the sun, hearing the waves—and someone who has only seen a beach in a magazine or online.

For the latter, the beach is just an isolated piece of data, a disconnected visual label. But for the person who has lived that experience, all the sensory details are immediately accessible.

That’s the difference between knowing about something and truly understanding it.

That’s why knowing the theory alone isn’t enough; you need to apply it on the guitar to truly understand it.

——————————————–

Information

This phenomenon becomes even clearer when we think about it in terms of language.

Consider the sentence:

“Many jacketed was guitar leather black beautifully playing the man.”

Each word might be familiar on its own, but together they fail to form a meaningful representation in our minds.

Now consider this version:

“The man in the black leather jacket was playing the guitar beautifully.”

Suddenly, the meaning is clear.

Why?

Because this second structure matches the linguistic patterns already formed in our brains, it activates a schema. The words don’t appear randomly; they follow a familiar and expected order.

The same is true in music.

Sounds only gain meaning through context, predictability, and relational structure. Music theory helps us analyze these relationships and become aware of the things we intuitively feel but can’t yet name.

Our ability to anticipate where a melody might go or to feel why a harmony is calming or tense depends on the richness of these mental representations. Music theory is not just a tool for analyzing, it’s also a tool for creating meaning.

Because meaning doesn’t only lie in what we play; it lies in what comes before and what follows after.

——————————————–

Shakespeare and the Chimpanzee

Meaning doesn’t emerge from randomness.

According to the infinite monkey theorem, given infinite time and resources, a chimpanzee randomly pressing keys might eventually produce a Shakespearean tragedy, but that doesn’t mean meaningful writing is the product of randomness. Likewise, randomly pressing notes on an instrument won’t result in a symphony.

Meaning arises through pattern.

Music theory gives us the ability to recognize, create, and refine those patterns. That’s the difference between a chimpanzee’s random keystrokes and a composer’s intentional choices: one is a statistical possibility within chaos, the other is meaning constructed through conscious structure.

Noodling on the guitar (just randomly playing around) feels a bit like Shakespeare’s chimpanzee.

If you’ve got infinite time, sure — it can be fun.

Yes, you do not have to know music theory, and you can engage with music purely as a hobby or for fun.

For this purpose, I share documents containing tablature for classical guitar pieces, aimed at those who enjoy classical works but do not know or do not wish to learn standard notation: Classical Guitar Pieces. With this series, you can play classical guitar pieces using only tablature, without needing to read sheet music. As I mentioned, I do not believe that learning notation or theory is an absolute requirement.

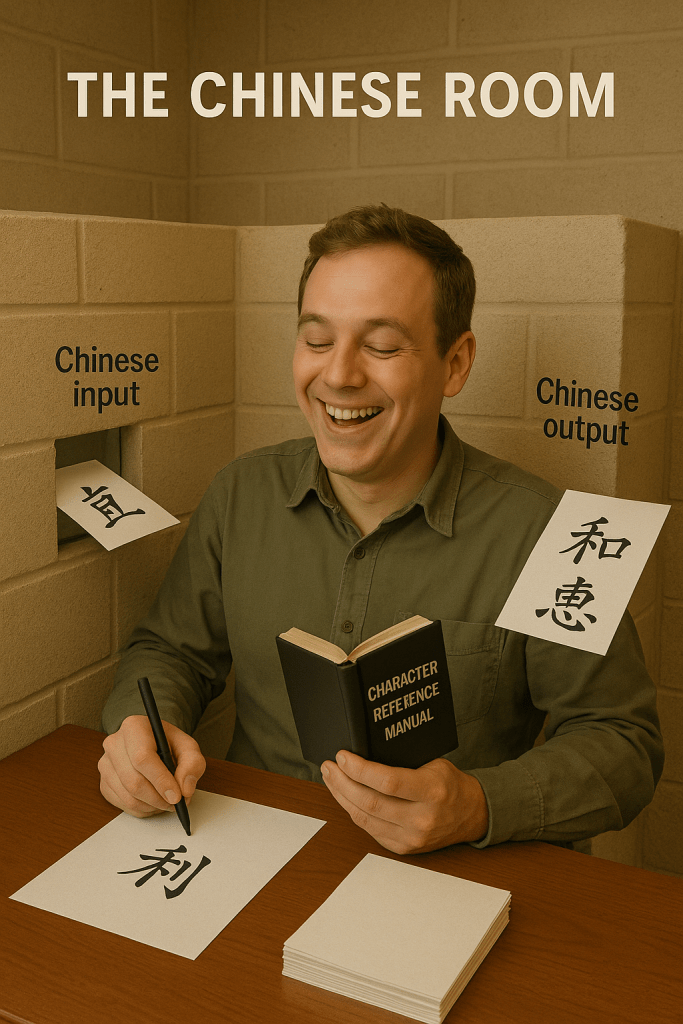

However, I compare this situation to the Chinese Room thought experiment:

——————————————–

Chinese Room

John Searle’s Chinese Room thought experiment, introduced in 1980, questions the difference between “truly understanding” and “merely producing correct outputs.”

In this thought experiment, Searle imagines himself in a closed room. He does not know Chinese, yet written questions in Chinese are passed to him from outside. By consulting a guidebook inside the room that contains Chinese question-and-answer rules, Searle provides responses. Even though he does not understand the questions or the answers, he produces appropriate outputs by following the instructions in the book.

The question of whether it is necessary to learn music theory intersects with this thought experiment. A musician may be able to produce melodies that sound pleasing, just as the person in the Chinese Room can generate seemingly correct symbols. Yet this does not mean that they truly “understand.”

Music theory helps us grasp the relationships between notes, the tensions, the resolutions, and the emotional contexts behind them. It is a way of giving meaning to sounds, beyond simply placing them side by side. In other words, theory transforms music from a purely mechanical process into an expressive form that is internally understood and deeply connected with feeling and thought.

Now imagine learning to play a piece only by following your teacher’s instructions, or playing a song you love by using the tablature from Songsterr. Or, if you want to see how deep the rabbit hole goes… ; )

——————————————–

The choice is always yours:

——————————————–

Leave a comment