Professor Vilayanur Subramanian Ramachandran, also known as the Sherlock Holmes of neurology.

He is a groundbreaking neuroscientist who has explored a wide range of topics, including phantom limbs and phantom pain. He also developed mirror therapy, a simple yet pioneering technique. He was the one who showed us that the brain is far more flexible than we once believed. His experiments showed that the brain is capable of deception, creativity, and improvisation that can rival even the best illusionists. His experiments with the mirror box challenged traditional views and expanded the reach of neuroscience into unexpected areas such as music, practice, and learning.

He first worked with Tom, a 17-year-old who had lost his arm in an accident. Tom’s arm had been amputated, and based on Edward Taub’s earlier experiments, it was expected that the brain maps responsible for the arm would eventually be taken over by nearby regions, especially those representing the face. To test this, Ramachandran blindfolded Tom and gently touched various parts of his body with a cotton swab, asking him to describe what he felt. When he touched Tom’s cheek, Tom reported feeling the sensation both on his cheek and on his phantom arm. When his upper lip was touched, he felt it not only on his lip but also on what used to be the index finger of his missing hand. Each spot on his face triggered a distinct sensation in a different part of his phantom limb.

Even more surprising, Tom discovered that he could relieve an itch in his phantom arm—something that had troubled him for a long time—simply by scratching his cheek. Later, advanced brain imaging confirmed what these sensations had revealed: the brain maps for the hand and the face had merged.

Remember the article about Unconscious Facial Expressions: the Homunculus.

But could a treatment be developed for people who had lost a limb long ago and were still experiencing itching or pain in their phantom limb?

When Ramachandran reviewed the case histories of these patients, he noticed a common pattern: many of them had their limbs immobilized in casts or slings for weeks before the amputation. It seemed that the brain had encoded this fixed position almost permanently into its internal maps.

This led him to a crucial question: Could the brain be rewired to overcome phantom paralysis and pain?

This was a question that targeted a condition rooted not in physical matter, but in psychological reality. It was the kind of problem usually explored by psychiatrists, psychologists, or psychoanalysts. Yet Ramachandran’s work began to blur the boundaries between neurology and psychiatry, and between what is real and what is imagined.

Then Ramachandran had an idea that felt almost like a magician’s trick. He wondered what if one illusion could be used to cancel out another? What if the brain could be fooled into thinking that a missing limb was moving, simply by sending it false visual signals?

This question led to the invention of the mirror box.

——————————————–

The Mirror Box

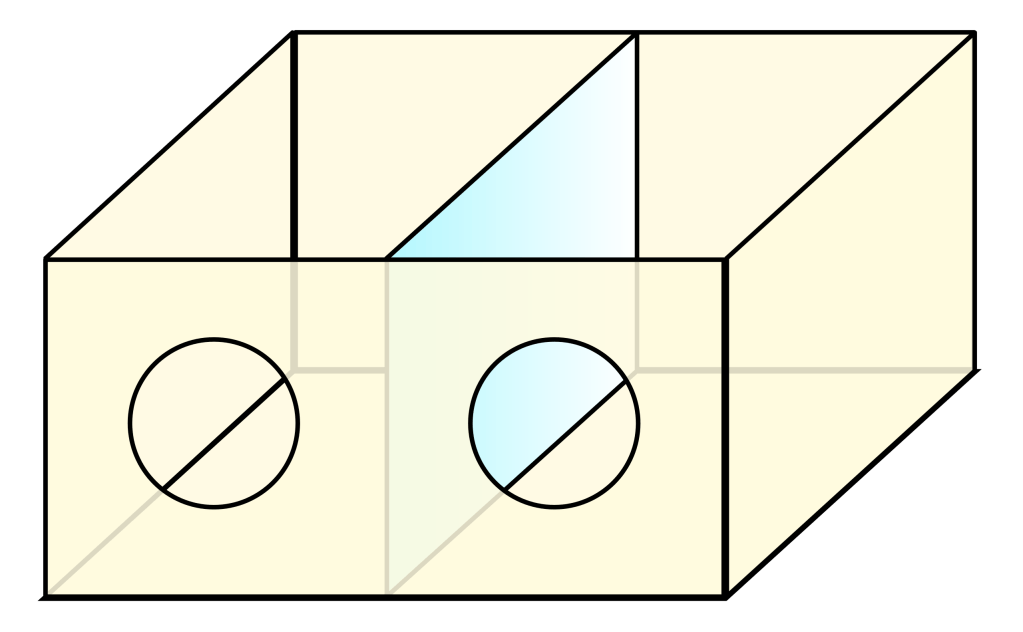

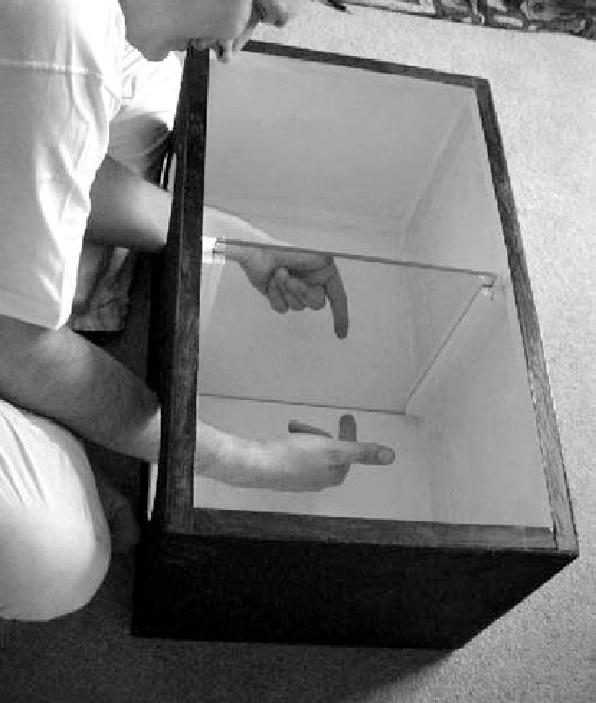

The mirror box was roughly the size of a large cake box. It had no lid and was divided into two separate compartments: one for the left hand and one for the right. At the front, there were two openings where the patient could insert their hands. If someone had lost their left arm, they would place their uninjured right hand into the right compartment and imagine placing their phantom left hand into the left side.

A vertical mirror stood between the two compartments, reflecting the image of the right hand. Since the box was open at the top, the patient could lean slightly to the right and see the reflection in the mirror. What they saw closely looked like their missing left hand.

When the patient moved their right hand back and forth, the reflection created the powerful illusion that the phantom left hand was moving too. Ramachandran hoped that this visual trick would convince the brain that the phantom limb was actually in motion.

——————————————–

Philip’s Story

Philip Martinez had a motorcycle accident ten years ago. The nerves in his left arm were severely damaged, and after some time, he made the difficult decision to have the arm amputated. What followed was an intense and constant phantom pain located in his left elbow. Although he couldn’t move his phantom arm, he had a strong sense that if he could just move it— even slightly— the pain might ease. This strange and frustrating experience gradually pushed Philip into a deep depression. At one point, he even considered taking his own life.

When Philip placed his remaining arm into the mirror box, he didn’t just see the illusion of movement, he actually felt his phantom arm moving for the first time. The experience had a life-changing effect on him. Overcome with emotion, he turned to Ramachandran and said, “My phantom arm is back!” The pain disappeared completely. But whenever he looked away from the mirror or closed his eyes, the phantom arm would freeze again, and the pain would return.

Ramachandran gave Philip the mirror box to use at home, hoping it would trigger plastic changes in his brain map and gradually help the paralysis fade. Philip used the box for just ten minutes each day. After four weeks, Ramachandran received an excited phone call. Even when Philip wasn’t using the mirror box, his phantom arm no longer froze. The sensation in his phantom elbow had disappeared, and the pain was completely gone.

——————————————–

Extending Mirror Therapy

Ramachandran later suggested that in patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS Type 1), the pain might not be purely physical. Instead, it could also act as a kind of defense mechanism, shaped by cognitive and motor systems. He tested the mirror box on these patients as well.

Patients would place both hands into the mirror box, though only the movement of the healthy hand and its reflection was visible. They were instructed to move the healthy hand—and, if possible, the affected one—at the same time, repeating the exercise for ten minutes, several times a day. This mirrored movement sent a clear message to the brain: “My injured arm is moving freely and without pain.” Over time, this visual feedback helped reshape the patient’s perception of their own body.

Indeed, some patients who had been living with CRPS for just two months showed significant improvement with this method. However, in cases where the condition had lasted longer than two years, little to no recovery was observed.

——————————————–

Mental Exercise and Plastic Change

Austrian scientist Lorimer Moseley hypothesized that mental exercises could benefit patients who did not respond to mirror therapy. He suggested that expanding long-term motor representations in the brain might lead to neural reorganization, also known as plasticity.

Patients were shown photographs of hands in various positions. They were asked to look at these images for 15 minutes, three times a day, while mentally simulating the movement of their own hands into the same positions. This mental exercise was followed by mirror therapy. After 12 weeks, some patients reported a reduction in pain, and half of them experienced complete relief.

Think back to the article titled If You Can Imagine It, You Can Do It.

——————————————–

Have you noticed?

These patients improved without any medication or surgery, just by doing 10 to 15 minutes of daily practice.

From this, two important ideas stand out:

- Just ten minutes of focused practice each day can lead to remarkable changes.

- Watching your hand in the mirror while practicing a new technique can help your brain pick up the movement faster and make learning more efficient.

——————————————–

Source:

Synaesthesia in phantom limbs induced with mirrors

Phantoms in the Brain: Probing the Mysteries of the Human Mind

Leave a comment