Have you ever noticed yourself frowning, pursing your lips, or clenching your teeth while playing the guitar, without even realizing it?

Facial expressions are typically involuntary muscle movements that reflect emotion. We often see them during the performances of guitarists we enjoy watching. Just as we naturally make facial expressions while talking to someone, we may also show what we feel through unconscious facial expressions while playing an instrument.

But what about the expressions that appear when you’re working through a difficult exercise or trying out a new technique on the guitar?

While the simulation theory of the universe is still up for debate, let me introduce you to a simulation region inside your own brain:

——————————————–

The Homunculus

Today, when we need to get to an unfamiliar place, we rely on navigation apps on our phones. As you know, these apps contain maps that represent real world locations. Basically, a map is a representation, a symbolic version, of something that exists in the real world. The map app on your phone gives you a digital version of an actual physical space. The brain has a similar internal map, commonly called the homunculus, the “little man” inside the brain.

This metaphor was introduced in the 1930s by neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield and his colleagues Edwin Boldrey and Theodore Rasmussen. They mapped brain regions by applying direct electrical stimulation to the cortices of awake patients.

——————————————–

——————————————–

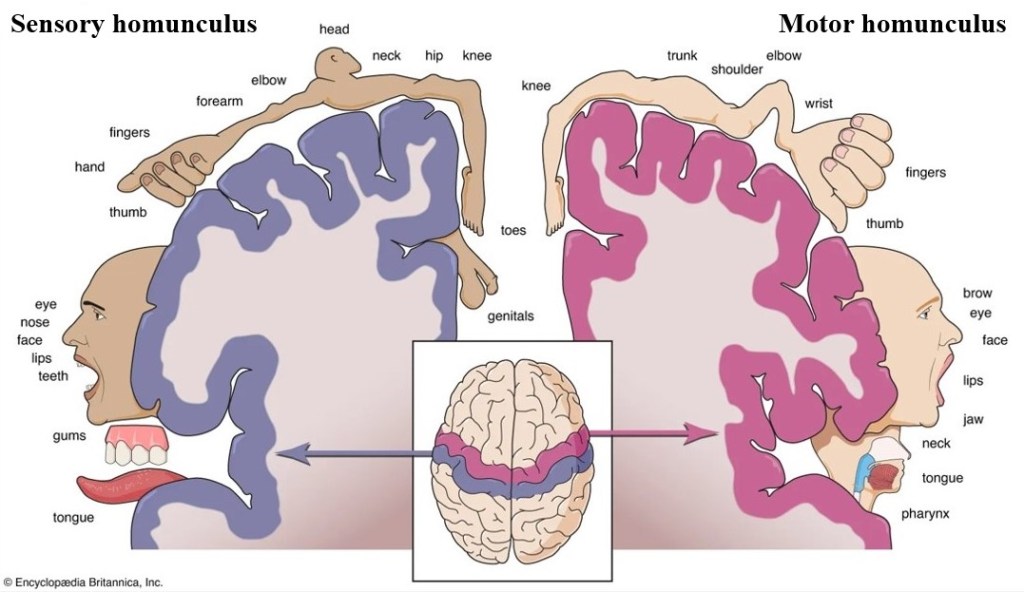

The Homunculus Appears in Two Forms on the Cerebral Cortex:

Somatosensory Homunculus

This version is found in the primary somatosensory cortex (S1) of the parietal lobe. It processes sensory input from different parts of the body such as touch, pressure, and proprioception (your sense of body position).

Key Features

- The amount of cortical space assigned to each body part depends on sensory sensitivity, not physical size.

- For example, the hands and lips take up far more cortical space than the back or legs.

- That’s why the somatosensory homunculus is often shown as a distorted figure with oversized hands, lips, and facial features.

Main Functions

- Touch awareness

- Proprioception (e.g., touching your nose with your eyes closed)

- Physical mapping of where the body is in contact with the outside world

——————————————–

Motor Homunculus

This version is located in the primary motor cortex (M1) of the frontal lobe. It maps the brain regions responsible for controlling voluntary muscle movements that is, which part of the brain moves which part of the body.

Key Features

- Just like the somatosensory homunculus, the amount of cortical space isn’t based on the size of a body part, but on how precisely it needs to be controlled.

- Areas that require fine motor skills—like the hands, fingers, and face—take up much more space than larger parts like the back or legs.

Main Functions

- Sending movement signals to the muscles

- Planning and starting fine motor actions

- Prioritizing control and accuracy over the size or force of a movement

——————————————–

The two homunculus maps work together. The motor and sensory homunculus maps run in parallel and constantly interact with each other. For example, when you play the guitar and press the strings with your left hand fingers, your motor cortex activates to move the fingers, while your somatosensory cortex processes touch, pressure, and finger position. With consistent repetition and focused practice, these brain maps change over time, a process called neuroplasticity. The brain’s representation of your fingers can grow larger and more sensitive. That’s how skills become automatic, eventually allowing you to “play with your eyes closed.” Repeated practice creates an internal model in the motor-sensory circuits. Your brain doesn’t just learn what the movement is, it also learns how it should feel.

This model isn’t set in stone, it changes with experience, repetition, and learning. This ability of the brain to adapt is called cortical plasticity. For example, musicians typically have a larger brain area dedicated to finger control in both hands compared to non-musicians. In a series of experiments, Pascual-Leone found that blind individuals who read Braille had an enlarged brain map for their right index finger—the finger they used for reading—compared to the left.

The homunculus reflects more than just neural mapping, it also reveals our evolutionary priorities. Body parts involved in essential tasks like communication and exploration, such as the hands, mouth, and tongue, take up a much larger portion of the brain’s cortical resources compared to their physical size.

Learning to play the guitar isn’t just about developing a musical skill. It’s also a process that rewires the brain. With time and practice, the strings, frets, and chord positions become more than sounds, they turn into patterns linked to touch, spatial awareness, and movement.

Just as you can touch your nose with your eyes closed, consistent practice enables you to find and play chords or notes on the guitar by feel alone.

——————————————–

So why do those unconscious facial expressions happen in the first place?

As mentioned earlier, the areas in the motor cortex that control the hands, fingers, and facial muscles—especially the lips and tongue—are located very close together. Because of this, a phenomenon called sensorimotor co-activation can occur.

In other words, when there is intense effort or focus directed toward the fingers, nearby facial muscles may become involuntarily activated as a side effect.

Leave a comment