Anna Mary Robertson began painting at 78 and gained worldwide fame.

Kimani Maruge started elementary school at the age of 84.

Nola Ochs earned her college degree at 95.

Fauja Singh took up marathon running at 89.

Tao Porchon Lynch became a yoga instructor at 80 and kept teaching until she was 100.

Bill Tapia released his first music album at 94.

Edith Murway-Traina started weightlifting at 90 and broke a record at 100.

Sylvia Holt began learning the cello at 70; within three years, she was performing with amateur chamber music groups.

Takashi Tanaka started playing the piano at 80 and gave his first recital at 85.

Wally Boot began playing drums at 73. He had always loved rock music but never played. He joined weekly jam sessions at a local center in his seventies.

Mary Ho picked up the guitar at 60 and became known worldwide through the internet at 80.

Alan Tripp composed music at 90 and released an album with his own band at 102.

Patricia Guiterrez started learning chords on YouTube at 65 to inspire her grandchild, and joined a local guitar group by the time she turned 70.

And the list goes on…

——————————————–

Years ago, I received an email from someone who wanted to take guitar lessons. The sender was a professor in his fifties. He shared that he had taken lessons for a few months during college but had to stop due to a demanding schedule. He had always dreamed of playing, but somehow, that passion had never become a reality. He sent me a short list of pieces he hoped to play before he died, and simply asked: “Would you be able to help?”

Between constant business trips, raising two children, and competing regularly in tennis tournaments, he was the very definition of “being busy.”

We began the lessons…

We had just passed the two-year mark of regular lessons when a notification popped up on my phone. As always, I had asked him to send a practice video sometime during the week. In this one, he was playing one of the very songs he had listed in that first email : )

After working with students aged five to sixty over the past twenty years, I can say this with confidence: When it comes to mastering a technique, focus is just as important as age. Yes, the brain’s capacity for plasticity is much higher in early childhood and tends to decline with age. For this reason, there are programs such as the Suzuki method, which aim to provide instrumental education especially at an early age.

But one powerful factor can turn that pessimistic view on its head:

Your lifestyle and habits.

——————————————–

”The same changes we see in young brains are also possible in older brains”

In childhood, we go through an intense period of learning. Each day is filled with novelty. In the early years of adult life, we remain actively engaged in learning and acquiring new skills. As we grow older, we begin to apply those abilities. By middle age, life tends to become more structured and predictable. Unless disrupted by unusual circumstances, this phase is generally calmer than childhood or adolescence. Our bodies no longer experience constant change, as they did during puberty. We tend to have a clearer sense of identity and navigate our careers with greater confidence. We still think of ourselves as active learners, yet we often assume that we’re learning the way we always have. We believe that, after years of education, we’ve “earned the right” to simply live.

In our younger years, we actively worked to expand our vocabulary and acquire new skills. But over time, we stop engaging in activities that sharpen our focus and we believe that our work is enough of a challenge. However, performing a job we’ve done for years or speaking our native language mostly relies on the repetition of well-established skills. By the time we reach our seventies, we may not have meaningfully engaged the brain systems responsible for plasticity in nearly forty years. This is why learning a new skill at that stage can feel difficult: the brain has become more rigid, and we tend to stay in our comfort zones, living life on autopilot. This is the dark side of plasticity: Neuroplasticity can lead to either flexibility or rigidity, depending entirely on how we use our brains.

According to Michael Merzenich, everything we observe in a young brain can also happen in an older one. The only essential requirement is the ability to sustain focused attention, which is powered by the brain’s reward system. When that condition is met, meaningful changes can occur in the brain at any age. What’s more, while younger people often struggle with focus due to a constant stream of internal and external distractions, a physically and mentally healthy older adult may actually have a much stronger capacity for sustained attention.

——————————————–

The Miracle of Neural Stem Cells

In 1988, Frederick Gage and Peter Eriksson discovered neural stem cells in the hippocampus. These cells were visibly vibrant and full of life. They were named neural stem cells because they had the ability to divide and transform into either glial cells, which support neurons, or neurons themselves. What made these cells truly remarkable was their capacity to self-replicate and keep dividing again and again, regardless of age. That’s why stem cells are often described as the brain’s forever-young “baby cells.” This continuous renewal process, which lasts a lifetime, is called neurogenesis.1

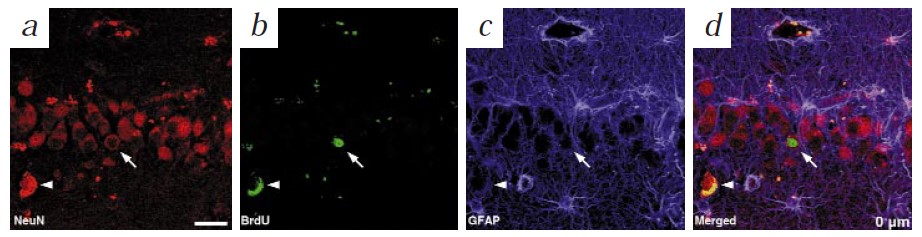

a) NeuN (red): A specific marker used to identify neurons. b) BrdU (green): Highlights cells that have recently divided, indicating active proliferation. c) GFAP (purple): Marks glial cells and helps separate them from other cell types.

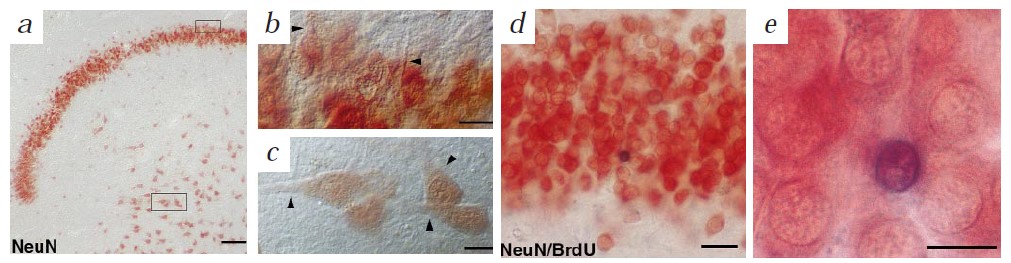

a) General NeuN staining observed in dentate granule cells and the hilus b–c) Detailed morphology of dentate granule cells and hilar neurons d–e) Double-labeled cells showing BrdU and NeuN overlap, indicating neural stem cells differentiating into neurons

Over the course of 45 days, Gage conducted a study on aging mice by placing them in enriched environments with stimulating objects such as balls, tubes, and running wheels. When their brains were examined, researchers found a 15% increase in hippocampal volume compared to mice raised in standard cages, along with the formation of approximately 40,000 new neurons.

Mice typically live around two years. Remarkably, when the team tested even older mice that had spent the second half of their lives (about 10 months) in enriched environments, they observed a fivefold increase in hippocampal neuron count. Although the older mice did not generate new neurons as quickly as the younger ones, they still produced them. This demonstrated that neurogenesis is possible even later in life. The study provided strong evidence that long-term mental stimulation plays a key role in promoting neurogenesis in the aging brain.2

The team then investigated which activities contributed to the increase in neuron counts in the mice’s brains. They found that there are two main ways to boost the total number of neurons: One is by generating new neurons, and the other is by extending the lifespan of existing ones. Generating new neurons is closely linked to physical exercise and exposure to new environments. In contrast, prolonging the life of existing neurons depends on learning and regularly practicing new intellectual or skill-based tasks.

The more educated we are, the more physically and socially active we remain, and the more we engage in mentally stimulating activities, the lower our risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of dementia. However, not all activities offer the same level of benefit. People who take part in cognitively demanding tasks—such as learning a musical instrument, reading, playing board games, or dancing—tend to show a much lower risk of cognitive decline.

The Harvard Study of Adult Development reached a similar conclusion. As part of the research, 824 individuals were tracked for more than 75 years, beginning in early adulthood. The findings challenged the common belief among younger generations that aging is simply a process of decline and deterioration. According to the study, many older adults continue to develop new skills and are often more knowledgeable and socially skilled than they were in their youth. They also tend to experience lower rates of depression and, in most cases, avoid serious illness until the final stages of life.3

——————————————–

I’ll conclude by recommending an excellent documentary on the subject:

——————————————–

When cellist Pablo Casals was 91 years old, a student once approached him and asked,

“Maestro, why do you still keep practicing?”

Casals simply replied,

“Because I’m still improving.”

——————————————–

Source:

1- Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus:

https://www.nature.com/articles/nm1198_1313

2- More hippocampal neurons in adult mice living in an enriched environment:

https://www.nature.com/articles/386493a0

3- Harvard Grant Study

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grant_Study

Leave a comment