“Learning is an emotional act.”

This sentence from a book I once read really made me pause and think about it.

I had always thought of learning as a rational, analytical, and strategic process. After all, that’s how education was presented to me throughout my school years. But how much of the information I was forced to absorb just to pass a class did I truly learn? That question marked the beginning of a new kind of awareness.

Then I remembered the times I began learning something with great excitement, but ended up quitting halfway through. Sometimes I lost motivation. Other times, my enthusiasm simply faded. In every case where I became deeply interested in a subject or skill and found myself reading or practicing for hours, that drive was always rooted in emotion. Likewise, walking away from something that no longer stirred any feeling in me, and doing so without regret, was emotional too.

I often compare this to a sailboat. Learning methods are undoubtedly rational and analytical. They’re the rudder and the technical framework of the boat. But no matter how perfectly built the sailboat is, if there’s no wind, it remains still, in all its glory…

That wind, the force that gets you started, keeps you going, or even makes you stop altogether, is called dopamine.

So let’s take a closer look at what this wind really is.

——————————————–

The Olds-Milner Experiment: The Brain’s Reward Button

In 1954, James Olds and Peter Milner conducted an experiment that would go on to change the course of neuroscience. Their original goal was to investigate how certain brain regions contribute to learning. But unexpectedly, their research uncovered a fundamental insight into the brain’s reward system.

Olds and Milner implanted an electrode into a rat’s brain and delivered electrical stimulation to specific regions. They then introduced a button. Each time the rat pressed it, it received a brief electrical pulse through the implanted electrode. This phenomenon became known as intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS), which refers to the brain being rewarded from within.

The findings were striking.

The rat was willing to press the button thousands of times just to self-administer the electrical stimulation. In fact, this drive was even stronger than its natural need for food or water.

These findings not only laid the groundwork for future research on learning and addiction, but also guided scientists to explore the role of neurotransmitters, particularly dopamine, in shaping how we perceive rewards.

This study led to the identification of the dopaminergic system as the brain’s natural reward circuit.

——————————————–

The Pathways of Dopamine in the Brain

To understand why learning sometimes feels enjoyable and at other times like a struggle, it helps to look at how dopamine moves through the brain and which areas it affects. And if you’re thinking, “That’s enough science for me,” here’s the short version: When things feel difficult, simply visualizing your goal can make a difference.

But for the curious minds saying, “If I understand not just the guitar, but also myself, I can learn more consciously,”—let’s keep going : )

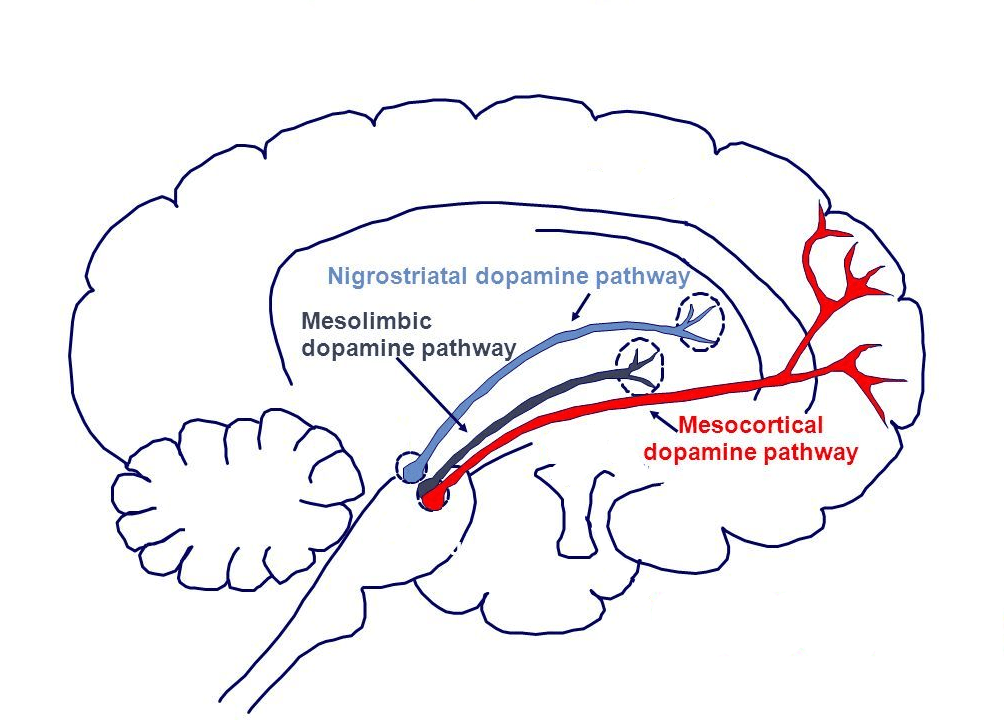

Dopamine is mainly released from two sources, travels along three primary pathways, and reaches different areas of the brain. Each pathway has distinct effects, depending on where it starts and where it ends.

By understanding these routes and how they work, you can manage the emotional ups and downs that come with learning more effectively. And in doing so, you’ll realize that self-awareness is just as important as raw talent.

The Mesolimbic Pathway

Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA) → Nucleus Accumbens, Amygdala, Hippocampus

The pleasure of playing the guitar, the satisfaction you feel when you successfully play a new piece, and the motivation to practice it againare all connected to this system.

When dopamine is released in the nucleus accumbens, it sends a powerful signal: “That was good. Do it again.”

For example, when you play a song:

- Nucleus Accumbens: “I enjoyed that behavior. Let’s do it again.”

- Amygdala: “This behavior is associated with positive emotions. It matters.”

- Hippocampus: “I’ve recorded this experience. I’ll link it to the context next time.”

The motivation cycle relies on the smooth functioning of this system.

The Mesocortical Pathway

Ventral Tegmental Alan (VTA) → Prefrontal Korteks

This pathway, which extends to the prefrontal cortex, plays a key role in strategic planning, error analysis, and setting long-term goals during guitar learning. Decisions like memorizing the chords of a new song, creating a practice schedule, or choosing which technique to focus on are all guided by this system. It also supports mood regulation, helping you stay motivated and emotionally resilient. In this region, dopamine contributes to processes such as cognitive flexibility, goal-directed focus, and effort regulation.

This region becomes especially important when you’re just starting to play guitar, or when you’re practicing something like a chromatic exercise that doesn’t feel immediately rewarding. It’s important to remember that these exercises are stepping stones to the music you dream of playing. They might not feel satisfying right now, but over time, they are exactly what will make it possible for you to play the piece that inspired you to pick up the guitar in the first place. Visualizing yourself playing confidently and knowing that your current efforts are taking you closer to that goal can help trigger the dopamine release you need to stay motivated.

This is an important point, because I’ve had students who gave up at this stage just because they weren’t having fun. It was honestly sad to see such talented people walk away from something they could have gotten really good at.

The Nigrostriatal Pathway

Substantia Nigra → Striatum (caudate nucleus ve putamen)

This is the most important pathway for guitar playing, because it’s responsible for planning, initiating, and eventually automating finger movements.

In the early stages of motor learning, planning your movements takes more conscious effort. But with enough repetition, these actions become automatic. This shift is made possible by the striatum, which helps build what we call procedural memory. The putamen, a part of the striatum, plays a key role in learning motor skills that depend on repetition, like playing the guitar. It helps your brain select the right movement sequences while filtering out the wrong ones.

——————————————–

The Marshmallow Experiment

In the early 1970s, a simple yet powerful experiment transformed our understanding of human behavior.

Led by psychologist Walter Mischel, the study involved children who were each offered a single marshmallow as a reward.They were told that if they could resist eating it right away and wait for a set amount of time, they would be given a second one. The researcher then left the room and returned 15 minutes later.

During the waiting period, some children closed their eyes, turned away from the table, or talked to themselves in an effort to resist the marshmallow. Others, however, couldn’t hold out for more than a few minutes and gave in to temptation almost immediately.

Mischel and his team followed the children for many years, and what they observed was impressive. Those who managed to delay gratification and wait for the second marshmallow not only earned that extra treat at the time, but also showed higher academic performance, stronger social skills, better stress management, and healthier long-term habits later in life.

Choosing a future reward over instant gratification has been linked to long-term success.

But what made some children able to wait, while others gave in right away?

In later years, when the experiment was repeated with larger groups, it became clear that environmental factors, such as a child’s economic and sociocultural background, played a major role. In other words, the ability to delay gratification was shaped significantly by a child’s upbringing and surroundings.

——————————————–

So, What Does All This Have to Do with Learning and Guitar?

The dopamine system we talked about is part of the brain’s remarkable ability called neuroplasticity. In other words, the brain can change depending on the choices you make. People who quit smoking or overcome other addictions are able to transform their lives because of this very mechanism.

Whether learning feels enjoyable or difficult depends largely on how your dopamine system is wired and how well you can delay gratification, both of which are shaped by your lifestyle and daily habits.

Especially during the technical development phase, try to look at the exercises not as boring tasks, but as essential tools for growth. Approach them with awareness, and keep in mind the reasons we’ve explored so far.

Breaking down exercises you don’t enjoy into smaller segments, and celebrating the completion of each one to trigger dopamine release, can make the learning process much more manageable and even enjoyable.

Similarly, when you strengthen your ability to delay gratification and keep your focus on the bigger reward ahead, you start to change the way boring technical exercises affect you, both mentally and emotionally.

We are creatures that can stress themselves just by thinking, even when sitting on a comfortable couch. Yet our mindset and the way we think enable us to manage this stress, at least to some extent. Before you pick up your guitar to practice, pause for a moment and observe yourself. Throughout the day, most of what you do is driven by expectation: you expect yourself to drive well, to perform efficiently at work, and to meet daily goals. When you decide to practice guitar, you bring similar expectations with you. Your mind is still “noisy” from the day’s demands, and practice easily becomes just another task on your list.

Before you begin, try to reset those expectations. This is not a “task.” It’s five or ten minutes in which you have the chance to make music with this beautiful instrument. If you can quiet the ego and stop judging yourself, you’ll begin to enjoy each note. This naturally triggers dopamine release, helping you connect more deeply with the joy of playing.

This is where the sailboat catches its wind.

——————————————–

As Michael Merzenich once said:

“The belief that our brain’s potential is fixed and can’t be developed in meaningful ways is deeply destructive.

In reality, the cerebral cortex is constantly renewing itself to meet the demands of whatever task we give it.

The brain isn’t just an empty container we fill with information. It’s more like a living organism with its own sense of taste, one that grows and reshapes itself through proper nourishment and regular mental and physical exercise.

The brain doesn’t just learn,

It’s always learning how to learn.”

Leave a comment