At a recent workshop, the instructor responded to a question with a simple line:

“This happens thanks to muscle memory.”

And just like that, the topic was considered settled : )

But not for me…

It was a term I had heard countless times before, yet I had never truly questioned it. But when I finally started thinking about it, I realized how questionable the assumptions behind it actually were. I knew that muscles are activated by motor neurons, and I remembered that memory is processed in a brain region called the hippocampus.

So, what exactly is meant by “muscle memory”?

——————————————–

Muscles Don’t Have Memory

There is no actual memory storage in the muscles. In other words, muscles themselves do not retain information. The term “muscle memory” is purely metaphorical. What we call muscle memory is actually the result of:

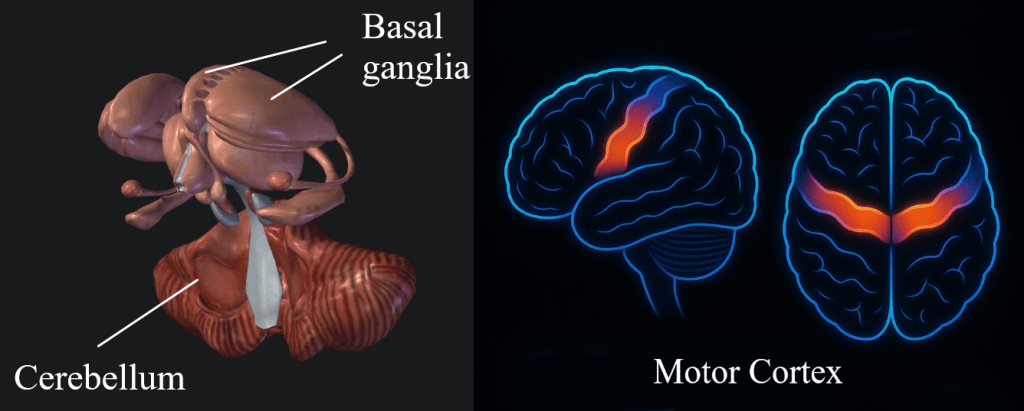

- Neural networks in the brain — particularly the basal ganglia, cerebellum, and motor cortex,

- Reflex circuits within the spinal cord,

- And procedural memory, which strengthens these pathways.

——————————————–

What Is Procedural Memory?

Procedural memory is a form of implicit (unconscious) long-term memory that enables us to perform tasks without being consciously aware of past experiences. It guides the actions we carry out, typically operating beneath the level of conscious awareness.

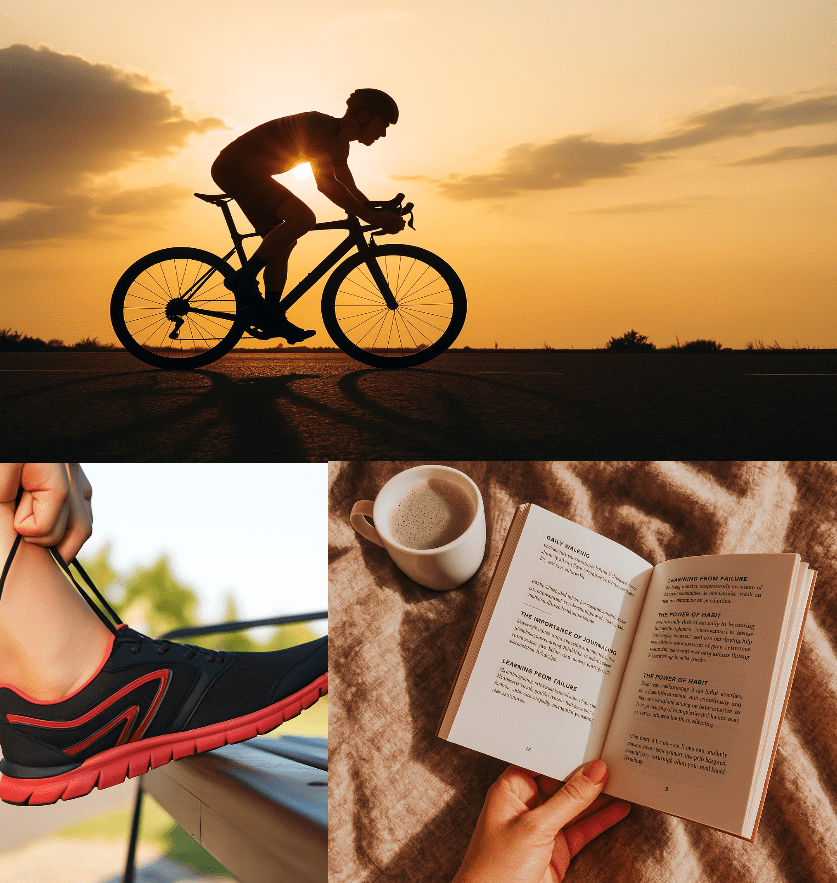

When needed, these memories are retrieved automatically and support the smooth execution of both cognitive and motor skills. Common examples include riding a bicycle, tying shoelaces, reading, or playing a musical instrument. Such skills are accessed and performed without the need for deliberate control or focused attention.

Procedural memory is developed through a process known as procedural learning. This takes place when a complex activity is practiced repeatedly, allowing the associated neural systems to work in coordination and eventually perform the task automatically. Repetitive practice is essential for the development of any motor or cognitive skill. (While it’s also possible to encode a skill into procedural memory through observation or mental rehearsal, that’s a subject for another article.) Each practice session helps transfer information into working memory, and over time, this information becomes embedded in procedural memory.

We often struggle to explain skills like riding a bicycle or driving a car. Instead of describing them in detail, we simply say, “Like this,” and demonstrate. This difficulty doesn’t come from so-called “muscle memory,” but rather from the fact that these advanced skills are no longer performed consciously, as explained earlier.

——————————————–

How Was Procedural Memory Discovered?

In 1953, a 27-year-old man known as H.M. underwent brain surgery to relieve the severe epileptic attacks he had suffered from since childhood. Surgeons believed that the source of these attacks was the hippocampus and surrounding structures, so they removed both hippocampi.

The surgery was successful in reducing H.M.’s seizures. However, an unusual complication emerged: he was no longer able to learn anything new.

He could recognize his family, recall childhood events, and scored within the normal range on intelligence tests. But when he met someone new, he wouldn’t remember them the next day. He held conversations with doctors for days, yet each time behaved as if meeting them for the first time.

However, his motor learning remained intact. In other words, he was still able to acquire new skills through practice. For instance, he improved at drawing a shape by looking at it in a mirror over time, although he had no memory of having done the task before.

Following the H.M. case, neuroscientists came to understand that the hippocampus plays a central role in transferring short-term explicit memory — information we consciously access — into long-term memory. While the hippocampus is essential for encoding new memories, it is not where they are permanently stored. Long-term memories are stored in the cortical structures. H.M.’s older memories remained intact because they had already been consolidated and transferred to the cortex before his surgery.

This case also helped clarify the difference between two types of memory:

- Explicit memory refers to events (episodic) and facts (semantic) that we can consciously recall. The hippocampus is crucial for forming this type of memory.

- Implicit memory involves unconscious learning such as reflexes, habits, and motor skills. It is supported by brain regions like the cerebellum and basal ganglia.

——————————————–

Skill Acquisition

To better understand how skills are acquired, Fitts (1954) and his colleagues proposed a model suggesting that learning progresses through a series of distinct stages.¹

1.Cognitive Stage: In this initial stage, attention plays a central role in acquiring the skill. The learner breaks down the task into smaller parts and focuses on understanding how those components fit together to perform the task correctly.

2.Associative Stage: This stage is characterized by repeated practice, during which recognizable response patterns begin to form. The learner becomes better at focusing on what matters. As practice continues, errors decrease and performance becomes smoother and more consistent.

3.Autonomous Stage: At this final stage, the ability to recognize and respond to relevant information becomes faster and more efficient. As the skill becomes automated, it requires minimal cognitive effort. Little to no conscious thought is needed, and performance becomes both rapid and consistent.

This is why I consistently emphasize the value of daily practice in my lessons. The exercises I’ve designed specifically for you are intended to develop the technical skills you need to play the pieces you dream of.

When you start working on a new technical exercise at the beginning of a lesson, it means you’ve entered the cognitive stage. At this point, the instructor introduces the purpose of the exercise and explains the rules of the targeted technique. By the end of the session, you should be ready to move into the associative stage. To support this transition, I often ask students to send videos during the week. This helps me check for any issues that may still remain at this ciritical stage.

With daily practice, the new technique gradually advances toward the autonomous stage. And if, while performing a technique that once felt difficult, you suddenly catch yourself thinking about what to have for dinner. Congratulations.

You’ve officially reached the autonomous stage : )

——————————————–

Factors That Support Procedural Memory

Sleep: Research shows that sleep plays a vital role in transferring newly learned skills into procedural memory. A full, uninterrupted night (or day) of sleep immediately following practice provides the optimal conditions for memory consolidation.²

Exercise: Regular physical activity or sports not only improve your mood by triggering the release of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, and endorphins, but also enhance your ability to focus and sustain attention for at least two hours after training. Additionally, they reduce overall reaction time. These effects are essential for helping the brain form and stabilize the neural pathways required for procedural memory.³

——————————————–

Final Words

After exploring all this research, I realized that my daily routine already matches these principles. It seems I’ve been doing a few things right, without even realizing it. For the past three years, my routine has been simple: a workout after work, followed by at least 15 minutes of guitar practice before bed.

Being able to play techniques that once felt difficult made me genuinely happy and deepened my connection with the guitar.

At the time, I thought to myself, “I guess I’m progressing smoothly thanks to muscle memory.”

But now, you know the real reason too.

——————————————–

References

1- Human Performance. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole

2- https://www.mdpi.com/2075-1729/14/2/203

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1074742721000824

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0896627302007663

3- https://nihrecord.nih.gov/2017/02/10/exercise-improves-mood-focus-aids-memory

Leave a comment